There is a cool subreddit that I digitally stumbled upon called r/Naturewasmetal. Two things:

- Metal?

- Was?

But how apt that name is! After perusing, I learned that the group venerates extinct dinosaurs and megafauna. Users upload scientific/artistic renderings of awesome creatures, both recently and long extinct. It’s both “bro”-y and forlorn. Like, “Look at this sick, oversized reptile! Nothing we have now can compare…”

As a champion of romanticizing the past, I support this group’s project. And as a narcissist, I appreciate its commitment to posting more recently extinct mammals. I think that when most people think about extinct animals, dinosaurs are the first that come to mind. And to be sure, the supreme K-Pg mass extinction event and the animals it killed were quite impressive. They deserve the attention. But looking at mass extinction solely through dinosaur-colored glasses reinforces a false sense of detachment from this type of event. While most people recognize that extinction is ongoing (largely driven by humans), I don’t think they realize just how recently large-scale extinction events have occurred.

Paleontologist and mammalogist Ross MacPhee does, though. I had the pleasure of meeting him a few weeks ago, after he generously offered to give my friends and me a tour of the current elephant exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). Ross works at AMNH and curated the exhibition. I had seen it twice before, and my first visit is actually what motivated me to start writing this. Going through it with Ross, though, was a whole other experience. I listened as he described the intention behind every component of the exhibition, sharing his personal thoughts and expounding the behind-the-scenes conversations that went into making it.

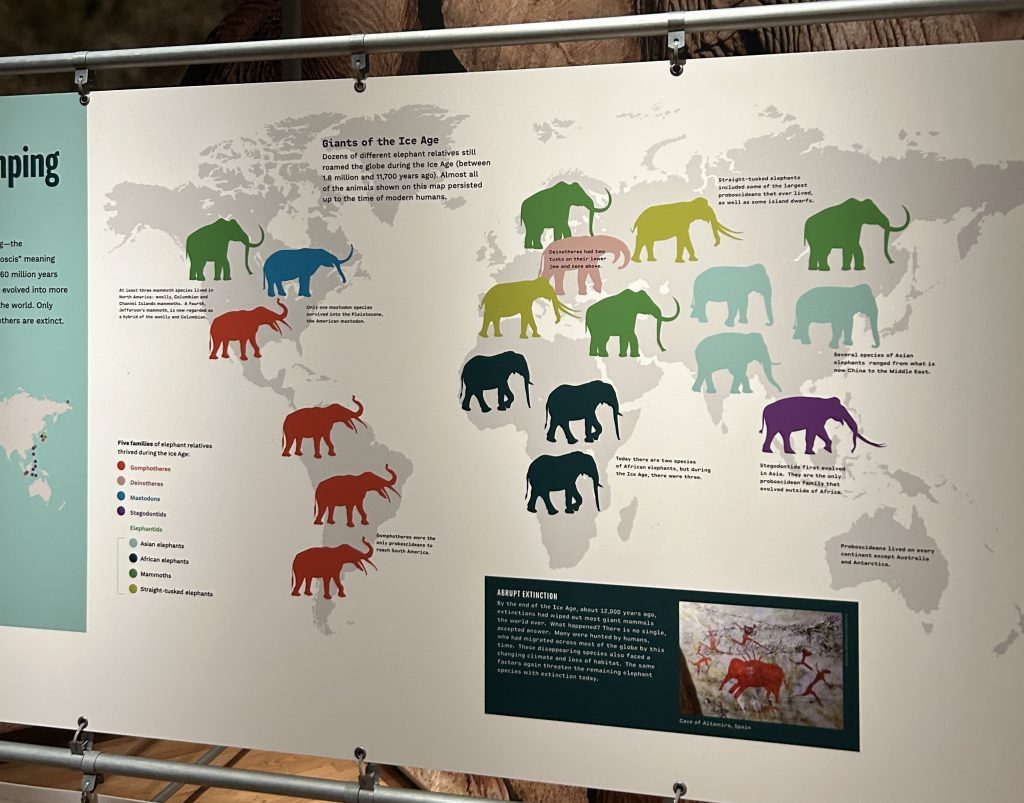

What struck me most about Ross’s elephant exhibition–and what kept me coming back–was the beginning. The first time I visited, I was alone. I had no expectations; I only went because I’m a museum member and can see ticketed exhibitions for free. But when I walked in, I almost immediately came to a stop. In front of me was a map of the world with elephants all over it, on every continent except Australia and Antarctica. I realized that this exhibition’s scope was broader than I had imagined. And sure enough, at the bottom of the map was a text box reading, “ABRUPT EXTINCTION: By the end of the Ice Age, about 12,000 years ago, extinctions had wiped out most giant mammals […]. What happened?”

My eyes were glued to the wall. I couldn’t look away from the panels scrutinizing proboscidean genomics, or those articulating elephant relatedness to sea cows. Reading each piece of text, studying each cladogram felt like an act of devotion. Yes, I thought, no one talks about this! They were here! They were right here! I was reading a panel on shovel-tuskers when I looked up and finally saw it, the visual apotheosis of all my wildest dreams: a life-sized woolly mammoth. It took me a few moments to register: the curved tusks, the clumps of matted fur, the small eye like a peephole. So like the animals encased in glass dioramas just a few halls down, yet so different; for one thing, none of its components could have been “real.”

Does this matter? True taxidermy has the elusive ability to blur the line between real and fake. It can produce a compelling mixture of both and neither–an elevated reality: a hyper-reality. But here was a complete fake! I think of Italian semiotician Umberto Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality, in which he describes Americans’ quest for the “real thing.” To attain it, he argues, we must produce the “absolute fake.” In other words, to copy reality, we must produce an absolute unreality, e.g., a faux-taxidermied mammoth. But let’s not forget that I’m American. Therefore, I LOVED it.

You may think that I love all taxidermy (considering how much I write about it), but that’s not true. I have never lent much credence to the idea that taxidermy can teach us to care. How will seeing a stuffed tiger help me empathize with the unique struggle of this species, of this animal? It won’t. And how can it teach me science? Will it impart knowledge to me otherwise unimpartable? This is what H. F. Osborn (eugenicist and onetime president of AMNH) thought, but I don’t. Furthermore, with the advent of photography, videography, holography, I think we are approaching truer means of representation. If what we’re searching for is realism, there are better options than taxidermy.

I’m beginning to believe, however, that realism is not the goal. Science and technology scholar Donna Haraway maintains in “Teddy Bear Patriarchy” that in an authoritative setting like a museum of natural history, we’re invited to suspend our disbelief. Participating in the make-believe of the museum, we gaze into dimly lit, stagelike dioramas and lock eyes with a specimen. She describes this experience as a sort of “communion with nature.” I must admit, I never quite received this sacrament. I rarely feel transported in time and space. The traces of the real to be found in taxidermied specimens and their display cases stand out to me and override any other state of reality that might otherwise be conjured.

The fake woolly mammoth is different. I could have never conceived of this display. The American Museum of Natural History recreating one of North America’s most iconic extinct megafauna–in the process of shedding its winter coat, no less–to stand guard at the forefront of an exhibition on its charismatic, extant relatives left me dumbstruck. The mammoth gatekeeping the elephant exhibition…how brilliant! For this extinct creature, the taxidermy felt absolutely necessary. No mere drawing or fossil recreation could have captured the majesty before me.

John Berger writes in “Why Look at Animals” that zoos testify to the impossibility of encountering wildlife in our day-to-day lives. To an extent, I agree. I even cited this idea in my undergraduate thesis. But improbability is not the same thing as impossibility. While most people will never meet, say, a lion in a non-zoo setting, that doesn’t mean it can’t happen. However unlikely, it still could. But meeting a woolly mammoth? This is an impossible encounter. Standing in the presence of a fake woolly mammoth brings to mind that fact and arrests the spectator.

The backdrop is eye-catching as well. Ross told me that he didn’t want to put the mammoth in a frozen tundra, an image with which we are all familiar. Instead, he wanted to place it in a springlike environment, hence the shedding. The model stands before a rocky riverbed. Water flows past a wall of coniferous trees, with no snow in sight. The setting appears neither bleak nor uninhabitable. It’s not unlike today’s national parks. It makes us wonder, could we have been here, too?

The craziest part is, Yes. While woolly mammoths and dozens of other proboscideans have gone extinct, humans indeed coexisted with them for thousands of years. Just over ten thousand years ago, we could cross paths. We did cross paths. It’s a little awkward, actually, because we partially induced their downfall (according to some hypotheses). The human-mammoth relationship is not neutral. So I look at this decrepit thing. My eyes comb its matted fur, and I peer into its watery eyes. The same forlorn quality of the extinction subreddit is definitely there. Bearing witness to a mammoth simulacrum, I wonder where we stand now.

Haraway compares AMNH’s Akeley Hall of African Mammals to a time machine. Specifically, she says it brings us to the moment of first contact, “the moment of interface of the Age of Mammals with the Age of Man.” Walking up to this mammoth brings us to another moment of interface–but not of first contact. Mammoths were pack animals, and this one is notably alone. Its winter coat is peeling off in clumps. Sickly-looking and solitary, the mammoth joins the visitor in “visual embrace,” as Haraway puts it. Indeed, we are passing from the Age of Mammals to the Age of Man, entering the Anthropocene. We are revisiting the origin, collapsing space and time and coming face-to-face with one of the largest North American land mammals. But we are not at the moment of first contact; this is the moment of last contact. The mammoth will soon, inexplicably, vanish. Walking past it, we enter the realm of the extant–the realm of the African and Asian elephant. We have exited the realm of unreality.

The rest of the exhibition is what you would expect. We learn about elephants and their anatomy and behavior and the ways that we exploit them and then the ways that we combat this exploitation. There’s actually a life-size figure of an elephant, just past the mammoth, with internal elephant organs projected onto its side. Its plastic body is visibly fake; it doesn’t try as hard to look real, and, frankly, it doesn’t need to. The “real thing” has never been out of reach.

At this point, I’m not sure if we are still supposed to be thinking about the mammoth. In some ways, the fake mammoth serves as a warning: if we don’t take conservation seriously, this could happen to our beloved elephant. Or the goal could be to underscore the ephemerality of all life on earth. Either way, the visual of that woolly mammoth has stayed with me. I wondered what kind of fur they used on its body. Ross wasn’t sure, but he guessed musk ox.

Bibliography

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” In About Looking, 3–28. London: Bloomsbury, 1980. http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/gustafson/FILM%20161.F08/readings/berger.animals%202.pdf.

Eco, Umberto. Travels in Hyperreality. Translated by William Weaver. New York: Harcourt, 1986.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” In The Haraway Reader, 151–97. New York: Routledge, 1989.

“The Secret World of Elephants.” Exhibition, New York, NY, November 13, 2023. https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/secret-world-elephants.

P.S. Did you know, the Asian elephant is more closely related to the woolly mammoth than it is to the African elephant? Subscribe for more cladistic fun facts!

Leave a comment